I’ve always been a big fan of artist’s fungus (Ganoderma applanatum), also known as artist’s bracket or artist’s conk. This shelf fungus is so named because if you scratch the white lower surface, dark marks are produced, and these are preserved after the fungus dries. I have only twice actually collected these fungi to draw on them; mostly I think they look nice right where they are.

I etched this first one almost twenty years ago. It has yellowed and faded some with age. The one below is almost as old, but looks just like it did when it was fresh. It’s a much larger one; I don’t know if that has anything to do with it, but it also was already hardened over much of its surface when I collected it, so that I was only able to draw on about a third of it.

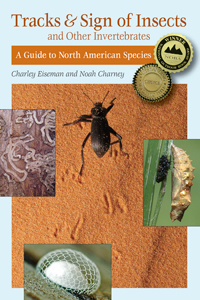

This year, every time I’ve encountered artist’s fungi there have been bizarre-looking, warty beetles on them. These are forked fungus beetles (Tenebrionidae: Bolitotherus cornutus), whose larvae apparently feed exclusively in Ganoderma fungi. Here’s one of the first group I saw, back on May 9:

The underside of this bracket was marred with nibble marks made by the adult beetles.

Three months later, on August 7, I found a cluster of small Ganoderma brackets that had strange, dark, flattened ovals, about 5 mm long, plastered onto their upper surface.

I strongly suspected that the beetles were responsible. I didn’t see anybody else around except this tiny thrips:

One of the ovals had a little hole in it that was about the right size for the thrips, and the thrips was near that hole when I first noticed it. But it didn’t seem possible that something as small as a thrips could have produced structures this large. I don’t think I noticed it at the time, but the beetle I photographed on this fungus has its face stuck in one of the ovals:

Thanks to an article* I found just now through BugGuide’s species page for the forked fungus beetle, I can confirm that these ovals are the beetles’ egg coverings, each one concealing a single egg. The article includes a photo of the coverings, and this description of their creation:

An egg was first deposited on its side on the fungus, and then covered by the excrement-like material composing the capsule. The female beetle deposited this material around the margin of the egg, and then smoothed it up and over the egg, using the soft, brushlike hairs on the tip of her abdomen. The capsular material was granular when first laid down, but these lumps were completely smoothed over. When first deposited, this capsule was dark, moist, black-brown, but dried to a lighter brown, similar to the color of the supporting fungus surface.

Looking at the capsule in the lower left corner of my photo above, it appears that the female at least sometimes nibbles the surface of the fungus to prepare it for egg laying. And my other photo seems to show the female chewing on the finished egg capsule, maybe to finish smoothing it, although it appears to be dry already. Incidentally, when I took my etched fungi off their shelf to photograph just now, I checked their upper surfaces, and each one had at least thirty of the egg capsules on it.

To summarize the life cycle as laid out in the article: The egg hatches in 11-26 days, then the larva remains in the egg covering for an average of five days, feeding on the capsular material. The larva then either burrows directly into the fungus, leaving the capsule intact, or bores a small hole in the top of the capsule and wanders around on the surface of the fungus for a while until it finds a crack or crevice, at which point it burrows in. So that’s probably what the hole I saw was, though I had assumed it was some kind of parasitoid wasp. The only parasitoid mentioned in the paper is a braconid wasp that parasitizes the larva once it is inside the fungus.

Larvae tunnel through the fungus for about ten weeks, then spend one to three weeks as a pupa. Freshly emerged adults generally rest in the pupal chamber for a few days, then chew their way out, leaving 6-9 mm-wide emergence holes. This species overwinters in both the larval and adult stages; including this dormant period, overwintering larvae remain as larvae for much longer than ten weeks: those that hatch in August emerge as adults in June. Eggs laid in June produce adults in September, which may survive until the following July or August.

So the one thing left to explain about these beetles is why they’re called “forked” fungus beetles. Well, on August 17 I finally saw some males, and it’s clearly the outlandish pair of appendages on the male’s thorax that gives the species its common name.

Pingback: Puffball Bugs | BugTracks

What are those dangly-thangies on the thorax appendages?? Does the “fringe on the surrey” help him sense, and how if so?

Oo, I think Kathie’s onto something–check out these videos (especially the second one), which she linked to in her article about these beetles.

I’m not sure… I think they’re just decorative, and I imagine the ladies go for the guys with bigger, furrier appendages, but I’ve never seen/heard anyone else suggest a purpose for them.

…Oh, well, I just looked around a little, and according to this, females don’t really care about the horns, but the males with bigger ones get to mate more because they use them to fend off or intimidate other males. So they’re like antlers. No mention of the hairy business though. I did just learn from that site, though, that these beetles can live up to five years!

Pingback: Postal conks :Cornell Mushroom Blog

I wonder if the furriness on the horns helps them get a good grip on their rivals? I linked to this fine post of yours here, Charley (and mentioned your awesome book).

Pingback: Postal conks | Cornell Mushroom Blog

Pingback: Monthly Mystery #14: Holes and Tunnels in Agave Leaves | BugTracks