This is the time of year that everybody is ragging on ragweed (Ambrosia spp.)—at least, everyone who realizes that it is the pollen of this plant, and not goldenrod, that is responsible for their summer allergies. At times like this, when some may feel like ridding the world of ragweed entirely, it’s good to remember that every native plant has a whole community of insects that depend on it.

Last August I noticed some striking little fruit flies (Tephritidae) hanging out on the ragweed in my yard:

These flies are Euaresta bella, whose only known host is common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia). The females lay eggs in female flowers and the larvae develop in the fruits, where they overwinter, pupating in the spring. The females in the last two photos above are on male flowers, which produce the dreaded pollen and presumably are not suitable oviposition sites.

Another species that feeds only on common ragweed is the leaf beetle Ophraella communa (Chrysomelidae). It lays clusters of yellow eggs on the foliage (these empty eggshells aren’t quite as yellow)…

…which produce hairy larvae that feed on the leaves.

Ophraella species are unusual among beetles in that they pupate in cocoons on their host plants (most beetles do not spin cocoons, and/or pupate in a cell hidden from view).

The adults are stripey and likewise feed on ragweed foliage.

Here’s an aphid that was sucking away on a ragweed stem in my yard last summer. It’s probably a Macrosiphoniella species, or possibly Uroleucon, according to Natalie Hernandez. Not being sure what it is, I can’t comment on its host specificity.

And then, of course, there are the leafminers. I count 30 North American species that are known or suspected to mine leaves of various ragweeds. Not all of these are specific to these hosts, but Astrotischeria ambrosiaeella (Tischeriidae) is an example of one that is. As far as I know it doesn’t occur in New England, but Julia and I found the distinctive mines on giant ragweed (Ambrosia trifida) at a rest area along I-70 in Missouri.

And then, of course, there are the leafminers. I count 30 North American species that are known or suspected to mine leaves of various ragweeds. Not all of these are specific to these hosts, but Astrotischeria ambrosiaeella (Tischeriidae) is an example of one that is. As far as I know it doesn’t occur in New England, but Julia and I found the distinctive mines on giant ragweed (Ambrosia trifida) at a rest area along I-70 in Missouri.

In the middle of the brown mined area is a green “nidus,” a silken retreat in which the larva ultimately pupates. The related species Astrotischeria heliopsisella, which mines leaves of sunflowers as well as ragweeds, eats the leaf tissue above the nidus so that it appears white instead of green. One of the mines in the above photo produced this adult moth:

The other mine produced this parasitoid:

The only chalcid parasitoid recorded from Astrotischeria heliopsisella is Pnigalio maculipes (Eulophidae). I think the one I reared is probably a Pnigalio, but probably not P. maculipes, since it doesn’t have the spotted legs that give that species its name. The genus Pnigalio needs revision anyway; the last set I gave Christer Hansson (reared from this eriocraniid) consisted of two species that couldn’t be identified using existing keys. Anyway, the point is, lots of bugs eat ragweed.

Hi Charley. Is there a source you would recommend on how to rear insects? You do it successfully all the time but mine always die in short order.

I guess I’m going to have to do a post at some point that details my methods, since I keep getting questions about that… I know there are some sources that describe rearing methods, but I’m not familiar with any of them and have just learned by trial and error. I’ll try to put something together this fall or winter.

Thank you for a continually interesting and understandable blog. I love it and I learn from it!

Euaresta bella lays eggs in the female flowers of Ragweed, these flowers have ovaries and would turn into fruit. Female flowers are in the leaf axils. I think what you are showing is the male flower spikes. No fruit would be produced there. If I may: Are you sure the fly was laying eggs there? Thanks for your great blog.

Ah, good point, thanks for noticing that. I’ll adjust my text accordingly. All of my photos of the females show them on flowers, but the flowers are all males so I guess it’s just a coincidence and they might as well be on foliage.

Again: thanks for your great blog!

Charley, I second the request for some rearing suggestions. I’d really like to avoid killing my ‘subjects of interest’.

I keep records of collected lepidoptera of Missouri. Astrotischeria ambrosiaeella has been recorded only twice in Missouri and both are literature records. The first is “Mem.Amer.Ent.Soc.28:78, 1972.”From Murtfeldt” [USNM]” and the other is “Forbes Lepid.N.Y. Vol. 1:” I would greatly appreciate it if you send the data from your specimen to me so it can be added to the database. There are over 204,000 records in the database and counting. If any researcher is interested in data of any species found in Missouri, just ask but be specific. My e-mail address is LepsofMO@yahoo.com.

Hi Charley,

I just started reading your blog posts. This one about the insects on ragweed felt especially locally relevant! I want to make a request that you give the size in your text post, for the insects pictured. That would be really helpful and wouldn’t make me have to go look for this information elsewhere. I’m lazy…

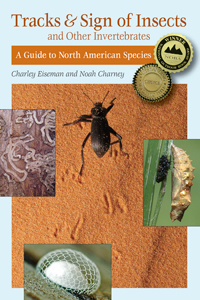

Thanks much for your excellent book and blog!

-Karen Arnett, in Cincinnati

Hi Karen– Thanks for the suggestion. I often do include the size in the text, but sometimes I’m lazy too. 🙂

Do you think anyone has ever tried to determine what makes these insects more resistant to the bio-chemical effects of ragweed pollen?

No idea! Though I suspect not, since as I understand it the effect on humans has no benefit to the plant and is purely accidental–a physical response rather than anything having to do with the plant’s chemistry (as suggested in the third paragraph here).

Pingback: Fixing the Lawn, Year 6 | BugTracks