Last week I was sitting with some friends around a campfire, making soup in a hollowed-out pumpkin. One of them was whittling away at a piece of a red maple branch when, suddenly, she got to this:

I have my friends trained pretty well, and she knew it was time to hand over that chunk of wood and look for something else to whittle. She had uncovered some tunnels of wood-boring beetles, but there should only be one larva per tunnel, and there are six visible in this one (each about 3 mm long). Presumably they are wasp larvae that have parasitized the beetle larva that made the tunnel–or else parasitized something else that had appropriated the tunnel. I covered them over with some sawdust and put the chunk of wood in the fridge for the winter, so with any luck I’ll be able to report back on what they turn out to be in the spring.

Meanwhile, I’m still slowly sorting through all the photos I took this past year, and last night I got to this one, taken in northern Vermont on June 28 (which means I’m now exactly five months behind):

This 5-mm beetle reminded me a little of a tumbling flower beetle (Mordellidae), so I guessed it was a member of some related family (Tenebrionoidea), but I couldn’t find a match. I posted it on BugGuide and went to bed. In the morning, I had my answer: it’s Pelecotoma flavipes, a wedge-shaped beetle (Ripiphoridae). Wedge-shaped beetles are among the few beetles that parasitize other insects. Relatively little is known about them, but as far as is known, members of the subfamily Ripiphorinae parasitize bees and wasps, their young larvae waiting for their hosts on flowers just as I observed a blister beetle larva doing this spring; the Ripidiinae parasitize cockroaches; and the Pelecotominae parasitize wood-boring beetles. The European species Pelecotoma fennica has been studied in detail, and the habits of P. flavipes are presumed to be similar. Females lay eggs at the openings of tunnels of death-watch beetles (Anobiidae) in dead or dying trees, and upon hatching the larvae enter the tunnels in search of their hosts. The Pelecotoma larva bores into a death-watch beetle larva and stays inside until the following spring, when it emerges and attaches itself to the outside of its host. It then grows rapidly, entirely consuming its host and then pupating in its host’s pupal chamber, emerging as an adult in late spring or early summer. (This information comes from Arnett et al. 2002, American Beetles, Vol. 2.)

The beetle in my photo is a female; males have fancy antennae. Pelecotoma flavipes is known to parasitize Ptilinus ruficornis, another species in which males have fancy antennae.

Very informative post. How full of “bugs” will your refrigerator be by spring? 🙂

We’ll see… So far just three items in the fridge, and about a hundred bags and jars that I put out in the shed yesterday!

This fall I discovered the calming awesomeness of whittling, and figured the big pile of brush & tree limbs in my backyard would be more than enough to keep me busy. Except that every time I went out rooting around for a piece of wood, I got distracted by all the stuff living under the bark. I rarely found anything I could use, because I didn’t want to evict anybody. Although all my poking was probably disruptive anyway… and one afternoon I could swear that a catbird was eyeballing the big juicy borer larvae and waiting for me to leave.

I just moved into a house with a wood stove, and I’m trying not to look too closely, otherwise I’ll never be able to heat the house! So far I’ve only had to set aside one log, which had an interesting poop-covered cocoon attached to it.

I know the feeling. We camp and cook at a fire pit on our acreage in the summer at a spot where beaver have cleared off most of the mature aspen and a couple of recent knock downs are the only source of large fuel within lugging distance. The down logs have a flat-headed borer (Dicerca callosa) that I can burn without feeling too bad, but also a neat ‘primitive’ wasp parasitoid (Orussus occidentalis) that I feel I should not be wantonly killing and lots of interesting little flies and what not. So, the logs are still laying there, the smaller limbs and kindling have been scavenged and burned (without dwelling on what was living in them), and next year I am going to have to develop a new ethos if I want a campfire.

Neat! I have yet to see an orussid. Do you have any photos of them?

I do have a mediocre point-and-shoot and some microscope shots. I’ll try to post them this weekend. The last two years Orussus occidentalis adults have been out in early spring around down aspen logs. You should have a species in your neck of the woods. They are boldly patterned and they jump! Which surprised me.

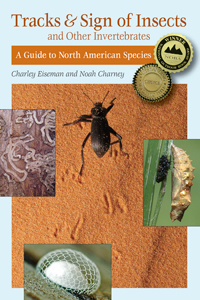

So we don’t want to look for leftovers in your fridge……Interesting stuff..I just ordered the book as I need a place to start looking for insects aside from the standard pretty stuff like butterflies, dragons and damsels..I do wish I had started this interest before middle age as my knees bother me now bending over to look at stuff…lol….Michelle

Your book is in the mail! I’ve found looking for tracks and signs to be a great window into the lives of all kinds of creatures I’d never paid much attention to before.

Pingback: Campoplegines, Part 2 | BugTracks

Pingback: Wood-boring Beetle Parasitoids, Part 2 | BugTracks

Pingback: Wood Boring Beetle Parasitoids | permaculturethinktank

Pingback: Fall Cleaning | BugTracks

Pingback: Wood-boring Beetle Parasitoids, Part 2 | BugTracks